What Henri Pirenne’s Mohammad and Charlemagne taught me about history

Maybe Medievalists are on to something

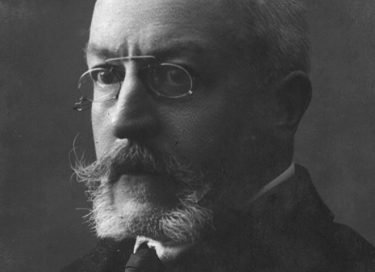

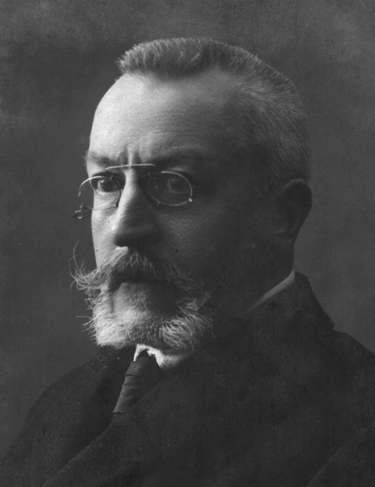

Henri Pirenne was a Belgian historian, medievalist, and public intellectual. He wrote numerous books in the early twentieth century, but the one I am going to talk about here is Mohammad and Charlemagne. Mohammad and Charlemagne was one of his more interesting books because of its ideas and arguments, but also because it was published posthumously. Indeed, Pirenne typically went through a process in which he wrote a first draft of a book and then almost completely rewrote the book as a second draft. In this book, Pirenne did not get past the first draft before dying, but someone thought it still worthy enough for publication. Imagine writing a book in one draft that ends up sparking a huge debate about European history!

The argument laid out in the book, or what is often referred to as the Pirenne Thesis, goes something like this:

The Germanic invasions of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries were not a significant break in history. The Roman Empire did not end at that point. The unity of the Mediterranean and connection between the East and West continued. Romania continued because the Germanic people wanted to be a part of the Roman Empire, not overtake it. Indeed, this Mediterranean unity or Romania had a sort of inertia to it. Despite the invasions, the institutions and norms continued unabated. Commerce continued, the monetary system continued, literacy continued, the Church remained relatively weak. There was still progress in thought and philosophy. What ended the Mediterranean unity and marked the beginning of the Middle Ages (and actual end of the Roman Empire) was the invasion by Muslims and the spread of Islam in the 7th and 8th centuries. Major commerce ended, the gold monetary system ended, many people became illiterate. The Middle Ages were beginning.

In some ways, the argument of the book is rather simple. Pirenne throws a lot of names, events, and developments at the reader, but what he was really trying to do was radically shift the periodization by adding several centuries to the history of the Roman Empire and antiquity. When it comes to the argument, I have little to say. I spend most of my time thinking, reading, and writing about American history. I know very little about the period Pirenne writes about and have almost no ability to contest his argument. The only things I could question were conceptual. Does the new periodization matter? Did the Germanic invasion mark the beginning of the end of Antiquity, but it just took a lot longer than people think? Was Pirenne being too normative (he really liked the culture of the Roman Empire and not so much the culture of Islam)?

Putting aside whether the Pirenne Thesis is correct, I think the work and the historian can still teach us a lot.

One thing that I learned while reading Pirenne is that he stream-of-consciousness style of writing is very useful. As I said, this book was only a first draft, and likely would have looked a lot different had it gotten the typical revision. However, I think there is a lot of value in reading the first draft. In it, Pirenne is somewhat informal. He uses personal pronouns a lot, and he frequently ask himself questions in the book, as if he is just talking throughout the book to himself. Historians don’t write like this today. Then tend to be very formal, they avoid personal pronouns when possible, and they assert their arguments. But I liked getting inside the mind of Pirenne and wish I could read more writing like his. Reading this book is like being there and getting to experience what it is like for a prominent historian to think through evidence and arguments in real time. It also just made the book easy to follow. It’s crazy how much more fun history can be when the author is a bit informal and less jargony.

Reading this book also demonstrates the value of writing in general. We often think we have good ideas when they are just inside our head. It is only when we begin to write (or talk to someone else about them out loud) that the ideas are contested, and thus become more refined through the process of writing.

Another thing Pirenne taught me is that historians can and should be bolder! Pirenne wasn’t making some sort of small argument about historiography. He didn’t deal with a particular person, or a particular event. Pirenne suggested that everyone was wrong when they considered the Middle Ages to have begun in the 5th century. This isn’t small fish. If you look up “Middle Ages” in google, you get a Wikipedia page that promptly tells you that the Middle Ages lasted from the 5th century to the 15th century. Pirenne disagreed and put it in writing! Throughout the book, Pirenne makes other bold arguments. For instance, on page 234 Pirenne claims that if it had not been for Mohammed, Charlemagne would have never been the person he came to be. This historian was not afraid to play with some contingency. And maybe he is wrong. But someone would need to think, research, and write about why he is wrong. This seems like a win-win to me.

Historians today tend to focus on small events or a short period of time. Furthermore, they tend to engage in arguments that bare little weight in the public’s imagination. Indeed, history books today are often written for a small group of historians who do the same work and argue amongst one another. And my aim is not to say that those are bad historians, or that they are writing poorly. But imagine a world in which more and more historians took on big arguments and tried to have an affect on not only their entire discipline, but other disciplines and the general public as well. Now, historians in their early career can be excused for not being bold. The job market is intense, and everyone wants to write a book that is convincing and highly acclaimed. But what about the tenured professors? They have almost complete academic freedom. Take a chance and risk being wrong!

Another thing that Pirenne has maybe taught me, or at least made me consider more fully, is the value of taking the longue durée view of history. This approach to history comes from the Annales School of history and it basically just means that we should view history over the “long term.” I had read a longue durée type of history before but did not put just a ton of thought into it. Part of the reason I’ve thought about it more has been the public interest in longtermism, as made more popular recently by the philosopher William MacAskill. If we want to stretch out our view of the future, shouldn’t we go further back when considering the past? Based on what I tend to see, less Americanists take a long-term view of American history. Part of the reason is the simple fact that American history is not that long. If you want to study American political history, you could start early with the first colonies. That gives us roughly 400 years of history. If you want to narrow it down to the United States government, the time span becomes even shorter. Meanwhile, a historian of the Middle Ages has a period of at least 1,000 years (unless we trust Pirenne).

So, what is the value of studying long periods of time? Presumably you would get a grander view of the sweep of history. Many developments take a really long time, and if we narrow in too much, I fear that we will miss the larger understanding that can come about from taking a long-term view of history.

Some of these lessons that I’ve taken from Pirenne might be obvious to other medievalist, but this was one of the first works that I’ve read on the period and place. As time goes on, I look forward to seeing what else I can learn from the European historians!