Occupational Licensing and Union Membership

Are licensing laws crowding out the need for unions?

For many Americans, the last few years were a period of economic uncertainty. With COVID-19 and the subsequent restrictions on economic activity, many faced the possibility of losing employment or the necessary clientele to remain in business. On top of the economic uncertainty brought about by the pandemic, inflation has been on the rise recently, cutting into wages and increasing the cost of basic necessities (although inflation does seem to be on the decline now). However, there is at least one silver lining in our current economy. While many have argued that the United States is currently in a recession, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic’s recent release shows a strong labor market. Indeed, the unemployment rate in the US fell to 3.5% in July and “total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 528,000.”

What this means for Americans in the labor market is that they might have more leverage than usual. Anecdotal evidence supports this idea. As many people have noticed, employers are desperate for good workers. If you’ve been to a restaurant or flown on a plane recently, you might be more than familiar with the shortage of labor (a college in my state, that I will refrain from naming, is trying to help).

As a result of this newfound leverage, workers are taking more time to find the best job possible, and in some cases leveraging their value to organize and demand higher wages. One place where this has manifested is at Starbucks, where the chain coffee store has experienced a wave of successful strikes (VICE). While the story of Starbucks unionization is far from over (Starbucks is closing 16 stores—and will likely close more), advocates of labor and unionization have hope that union membership may be on the rise.

An increase in union membership across the country would be peculiar, in part because union membership has been declining for so long and is at such a low rate. Indeed, despite union activity at Starbucks and Amazon, union membership overall continues to decline. While the percent of public sector employees unionized has hovered around 34% for some time, private sector union membership has recently dropped to a new low of roughly 6% (NYT). More than just Starbucks will need to unionize if the country is ever going to go back to the high levels of unionization in the past.

Many have attempted to explain the steady historic decline in union membership. In large part, the decline may simply reflect the changing US economy over the last 50-70 years. Employees in service jobs tend to be less unionized as compared to those working in manufacturing, and the US economy has transitioned to being a service economy while producing less goods.

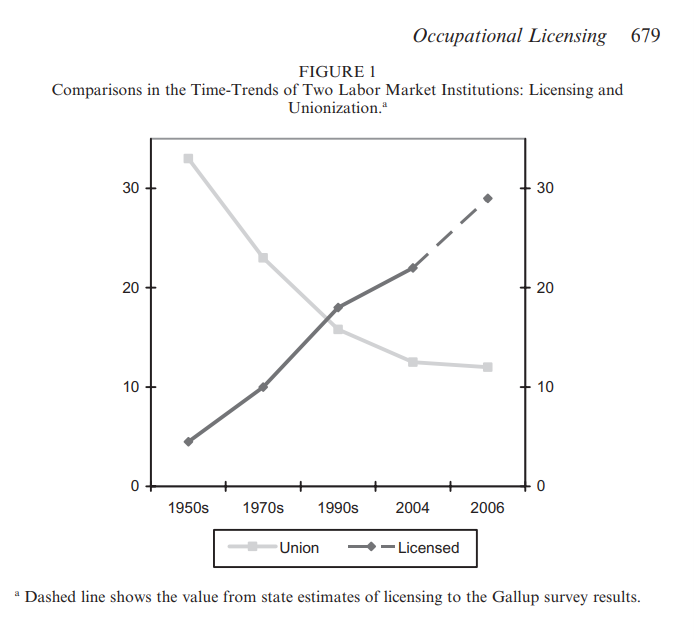

Others have argued that occupational licensing has played a role in the decline of union membership. In the last 60 years, the fraction of occupations that require a license has increased from 1 in 20 to 1 in 4 (NCSL). What does this have to do with unionization? While unions may vary from sector to sector and in different historical periods, they share some common characteristics. Unions have and continue to represent the interest of workers in a specific industry. Typically, this translates into employees using their collective power to bargain for shorter hours, higher wages, increased benefits, and the amelioration of other grievances. If occupational licensing sets up barriers to entry, thus increasing wages and benefits, decreasing the supply of workers, and giving workers more control over their hours, it could be possible that licensing is crowding out the need for unionization.

In a paper published in the Journal of Labor Economics, Morris Kleiner and Alan Kreuger explore the prevalence of licensing and the relationship between licensing and unionization. They find that, “the wage premium associated with licensing is strikingly similar to that found in studies of the effect of unions on wages” (S199). If licensing results in a similar increase in wages as compared to union membership, it might grant credence to the idea that licensing has replaced unionization. The graph below (included in the paper) does not prove that licensing is causing union membership to decline, but their certainly appears to be a relationship.

In my own research on the history of barber licensing in Arkansas, Dr. Marcus Witcher and I found that the International Journeyman Barber Union’s main goal throughout its history was to lobby for licensing laws in every state in the US (CATO). In research that has yet to be published, Dr. Witcher, Dr. Wendy Lucas, and I considered the degree to which cartel theory could explain this historical push for licensing (happy to share a copy of the paper to anyone interested). We argue that the barber union initially sought to cartelize the barber industry by urging barbers to voluntarily follow union practices. This would include staying open during “union hours,” charging “union prices,” and boycotting non-union businesses. If every barber followed suit, they could expect to increase their wages while working fewer hours. However, as cartel theory suggests it should play out (see Stigler), such schemes were ineffective. The reason is that each barber had an incentive to “cheat” the cartel. If every barber agrees to close at 5:00pm, and any one barber wants to make some extra cash, all they would have to do is stay open past 5:00pm. The same goes for charging lower prices that bring in more customers. Once one person cheats, it leads to more following suit, and thus a downward spiral of prices and an end to the cartel (note that this is bad for barbers—but great for consumers).

The reason voluntary cartels are unstable is that the organizing body has no actual power to enforce the desired norms. The barber union could boycott the “cheaters” but lacked any real teeth when it came to forcing shops to adhere to their favored business practices.

This is where licensing comes in.

If unions can secure licensing laws (each state currently licenses barbers), they can restrict the supply of barbers (thus increasing wages) and enforce standardization with the police powers of the state. While a union could not shut down a business, state licensing boards do have the power to revoke licenses and shut down schools and shops that don’t follow the state’s laws and regulations. Thus, licensing laws could serve the purpose of achieving what unions really want—a cartel. However, once a licensing law is secured, the need for a union seemingly goes away.

In fact, there were times when union organizers themselves recognized this. In the October 1955 edition of the Journeyman Barber Hairdresser and Cosmetologist (vol. 51, no. 10), union organizer W. H. Masson was sad to report, in an article titled “Too Much Government Assistance Can Kill Off Incentive,” that in in the city of Bull Moose (Saskatchewan, Canada), union membership had “dwindled to a mere handful.” According to Masson, the reason for the decline in membership “lies in the fact that barbers can secure that which they desire through government legislation.” The province of Saskatchewan was divided into zones, each with an advisory board, and if barbers in a particular zone wanted to change “wages, prices, etc., they may merely make application for such to the government through their advisory board.” As this situation made clear, “there is very little left for which a Union can contend [emphasis added].”

Of course, this example is from Canada, and the American situation is different. Barbers did not have the ability in the US to go to their licensing board and demand a change in wages or prices (though they did try to legislate prices—and were ultimately unsuccessful). However, the example does lay out the logical conclusion of successful licensing legislation. If barbers joined the union to achieve higher prices, and were granted the higher wages through licensing legislation, why waste your time and money on union dues? In fact, the Barbers, Beauticians and Allied Industries International Association’s (the union, like the journal, changed names over the years) history demonstrates this development. The last state to license barbers in the US was Alabama in 1971 (though numerous counties had a licensing board before 1971). By the mid-1970s, the largest barber union in the country was already on its death bed. Due to the acquisition of favorable legislation in each state (and to be fair, many other factors, including the proliferation of unisex chain shops, cosmetologists, and changing hair styles) union membership was dwindling rapidly. As a result, the union decided to merge with the much larger Food and Commercial Workers Union in 1980.

So, perhaps licensing laws have crowded out the need for unions. You might be asking, who cares? If licensing and unions lead to the same wage premium for workers, it doesn’t really matter which is there, right? Wrong. Licensing leads to the same wage premium as unions, but the similarities likely stop there. One major difference that Krueger and Kleiner point out (cited earlier) is that while unions reduce wage variation, “licensing does not appear to diminish wage variation” (S198). Unions organize workers in order to bargain for better wages from employers. If a union can increase the wages of workers, they hope to do so by bringing down the wages of employers. This, in turn, would serve to reduce income inequality. On the other hand, licensing does no such thing. Licensing offers workers the same wage premium, but it does so by restricting the supply of workers in the industry, thus doing little to ameliorate income inequality.

All of this is not to say that we necessarily need a resurgence in unions. In theory, I am happy to see workers organize (they do have a right to do so) and negotiate for their own interests. However, history also offers numerous examples of unions being a mixed bag (based on my anecdotal observations, historians tend to highly favor unions, and most Americans do as well, but for a historical counternarrative, consider looking into Paul Moreno’s, Black Americans and Organized Labor: A New History). However, everything I have said so far should suggest that licensing reform ought to be a bipartisan issue. Progressives and Conservatives claim to be representing and supporting workers, but they do so in different ways. Progressives tend to be concerned with income inequality and have a very high approval of union organizations. Conservatives don’t care so much about inequality or unions, but they do claim to be concerned about big government, taxes, and regulations. Given the competing interests, licensing reform would be a clear win-win. Progressives might see an uptick in unionization and income equality, while Conservatives could shrink the size of government and reduce regulations.

Though I argue that licensing has played a role in the historic decline in union membership, the full explanation is likely complex and multivariate. I am not fully steeped in the literature, but I would imagine numerous labor historians would have something to say on the topic too. Nonetheless, occupational licensing does appear to be playing a role, and might be a larger part of the puzzle than many would expect.