In the early twentieth century, the Journeyman Barber International Union of America was carrying on various activities. As we have argued previously, the barber union spent most of its time lobbying for restrictive licensing laws. The union could expect that once a licensing law was passed in a particular state, the supply of barbers would decrease, and thus the price of haircuts would go up (and the barber’s wages).

The push for licensing laws by barbers across the country was often motivated by the existence of barbers charging cheap prices. Indeed, the major barber union frequently complained of cut-rate shops where cheap barbers would offer services at prices below the union’s standards. In doing so, these “unprofessional” or non-union barbers cut into the business of union shops.

Though cheap barbers were often enemy number one for union barbers, another enemy emerged in the early twentieth century—the female barber.

The business of cutting hair was dominated by male barbers for most of the nineteenth century, but by the early twentieth, female barbers or hairdressers were beginning to cut into the market for beauty and hair styling. As females began opening shops and cutting hair, the Journeyman Barber Union had to make the decision of whether to allow women into the union.

At least initially, the union adamantly refused to allow women to join. At the 1914 Journeyman Barber Union convention, the union members voted to not allow women into the organization.[1]

In the Journeyman Barber Journal, barbers debated over what to do with the female barbers. One barber, Charles Rollo from Kansas, lamented that if women were allowed to join the union, “it would no doubt encourage more of them to enter the business” until they became so numerous that barbers would “quit the business entirely.”[2] The next year, the same barber frankly told his fellow union members to place their wives “at home in the kitchen where God intended her to be and then go after the pork chops yourself.”[3] Another barber simply opposed allowing women in the union “on general principles” since he believed that “a women is out of place in a barber shop.”[4] However, other barbers saw what the actual consequences of allowing women into the union would be. Henry Glenwood, showing a concern for keeping prices high, recognized that women “have been known to take men’s place for less money and I fear we are on dangerous grounds when we admit them.”[5]

There is a lot to be said about the resistance of male barbers to allow women into the union. Undoubtably, many men were simply sexist and did not think it right for women to be working at all, let alone in barber shops which were often masculine spaces. However, it likely that many barbers understood what Henry Glenwood understood—female barbers would bring down the wages of male barbers. This phenomenon of female entrants bringing down the wages of male workers has occurred in various industries. In 2016, a New York Times article highlighted the work done by Asaf Levanon, Paula England, and Paul Allison in which they show in a paper that “when women moved into occupations in large numbers, those jobs began paying less even after controlling for education, work experience, skills, race and geography” (NYT).

While the study above concluded that work done by women is simply valued less than work done by men, a simpler explanation (at least for barbers) might work just as well. Barbers worked in a very competitive market. Just consider what it takes to be a barber. You need skill, but beyond that you might just need basic tools of barbering and a room (shop or even a room in your home). A higher supply of barbers would result in more competition and thus lower prices and wages. Thus, allowing women to enter the industry in masses would threaten male barbers.

Despite efforts being made, barbers did concede that women could not be excluded from the industry and decided to make efforts towards simply segregating beauty shops by sex. For example, in 1925, the Long Beach hair dressers and cosmeticians’ association drafted an ordinance to “exclude women from barbers shops.” Consistent with union barber concerns, these barbers explained that the ordinance would “free male customers of barber shops of the annoyance and embarrassment of waiting while bobbed haired women monopolize the barber’s time and that, besides, a barber shop is not place for a girl.”[6]

In Alabama, similar attempts to restrict cosmetologists to only cutting women’s hair were made. In fact, the original Act number 403 which established barber licensing and a Board of Barber Examiners in 1971 specified “THE PRACTICE OF BARBERING” as involving shaving and cutting the hair “upon the human male body.”[7]

Many of the legislative efforts made by barbers to prevent women from cutting the hair of men were unsuccessful. As we would expect, these laws tended to be found unconstitutional for violating anti-discrimination laws.

While many of the efforts to segregate beauty and barber shops were superfluous or ineffective, the battle over clientele between men and women in the beauty industry at times could take a turn for the worse.

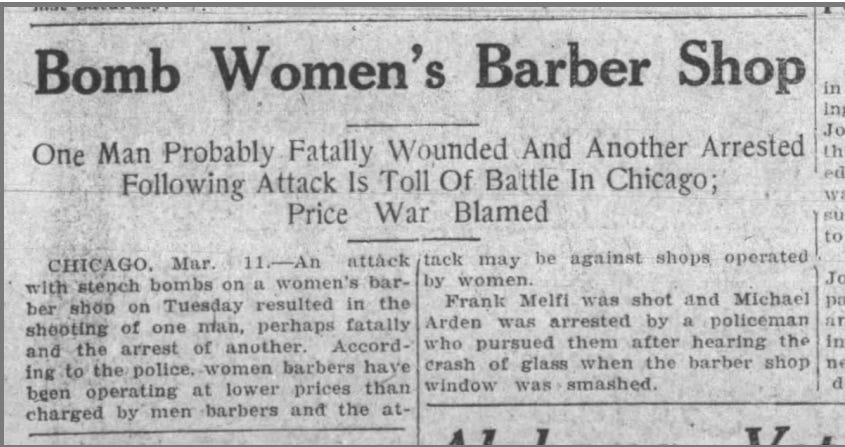

In 1925, the Selma Times-Journal reported “an attack with stench bombs on a women’s barber shop” in Chicago. Attempting to hurt the business of women running a barber shop, male barbers pulled the prank of “bombing” the shop with stink bombs. While the joke was perhaps supposed to hurt the women’s business without causing too much harm, it ended in the death of one of the attackers. Indeed, some nearby cops heard the glass window to the barber shop crash and pursued the two male barbers who “bombed” the women’s shop. In doing so, Frank Melfi (one of the two male barbers) refused to stop and was shot and killed by the cop. The other barber, Michael Arden, was arrested.

Though there could be multiple reasons for the attack, the newspaper cited prices as the culprit. Indeed, “according to the police, women barbers have been operating at lower prices than charged by men barbers and the attack may be against shops operated by women.”[8] As many barbers expected, female barbers were at times willing to charge lower prices to attract clientele that typically frequented male barber shops. In this case, the war over prices resulted in the death of one male barber and the arrest of another.

The story from Chicago may be an anomaly, but it reveals the strong desire amongst barbers to maintain their market share. Though this manifested in the push for licensing laws, laws that segregated shops by sex, and individual efforts to hurt the businesses of female barbers, they all represented the same sentiment of reducing competition.

[1] W. E. Klapetzky, The Journeyman Barber Journal 10, no. 10, “Notes and Comments,” November 1914, 478, Wisconsin Historical Society Library.

[2] Chas G. Rollo, The Journeyman Barber Journal 15, no. 11, “Correspondence,” December 1918, 468, The Wisconsin Historical Society Library.

[3] Charles G. Rollo, The Journeyman Barber Journal 15, no. 3, “Correspondence,” April 1919, 100, The Wisconsin Historical Society Library.

[4] Gus Rademacher, The Journeyman Barber Journal 15, no. 4, “Correspondence,” May 1919, 502, The Wisconsin Historical Society Library.

[5] Henry Glenwood, The Journeyman Barber Journal 15, no. 12, “Correspondence,” January 1919, 502, The Wisconsin Historical Society Library.

[6] “Would Exclude Women from Barber Shops,” The Nebraska State Journal, January 16, 1925, 3, newspapers.com.

[7] Act No. 403, 689.

[8] “Bomb Women’s Barber Shop: One man fatally wounded and another arrested following attack is toll of battle in Chicago; price war blamed,” The Selma Times-Journal, March 11, 1924, 1, newpapers.com.